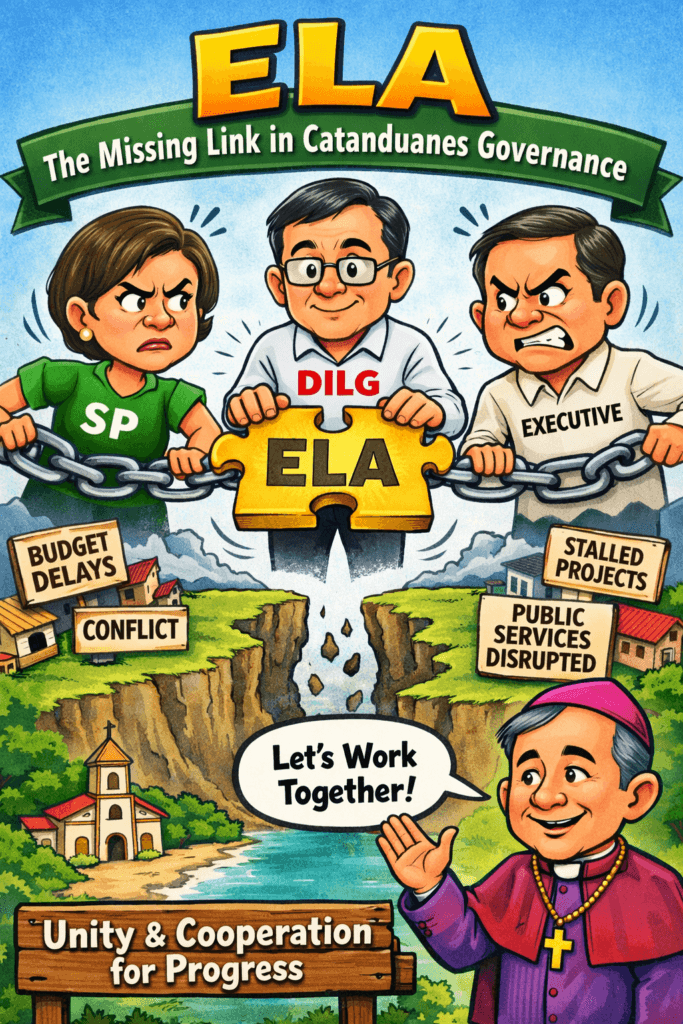

Amid the growing tension between the Sangguniang Panlalawigan and the Executive branch of the Provincial Government of Catanduanes, the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) has delivered a timely and crucial reminder: effective governance is not sustained by authority alone, but by structure, coordination, and shared direction. At the center of this reminder is the Executive and Legislative Agenda (ELA).

As explained by DILG Provincial Director Uldarico Razal Jr., the ELA is not a mere bureaucratic requirement. It is a jointly crafted roadmap developed by both the Executive and Legislative branches that defines the province’s development priorities for the next three years. Rooted in data and grounded on real needs, the ELA serves as a governance compass rather than a political manifesto.

Had an ELA been properly formulated and operationalized, many of today’s conflicts might have been avoided. Urgent executive appeals—particularly those related to disaster response, social services, and financial appropriations—would not have escalated into institutional standoffs if they had already been anchored on mutually agreed-upon priorities.

The strength of the ELA lies in its clarity of roles. The Executive identifies pressing concerns and development goals based on empirical conditions, while the Legislative translates these priorities into enabling ordinances and resolutions. This framework prevents governance from devolving into a contest of power and instead reinforces it as a division of responsibility.

The absence of an ELA meeting in Catanduanes to date exposes a critical gap in governance. While executive briefings were conducted during the early weeks of the officials’ terms, these cannot substitute a formal, inclusive, and institutionalized ELA process that demands shared accountability and sustained collaboration.

The consequences of this lack of coordination are now evident, particularly in the delayed passage of the provincial annual budget. Budget delays are not mere procedural lapses; they stall development projects, disrupt public services, and delay legally mandated benefits, including salary increases for government employees.

The DILG’s warning regarding the Seal of Good Local Governance (SGLG) further underscores the gravity of the situation. Timely budget approval is a fundamental governance indicator, and failure to comply reflects not only administrative weakness but a troubling disregard for public welfare.

In this climate of political strain, the call of Bishop Louie Occiano of the Diocese of Virac for a ceasefire carries moral weight. His appeal does not intrude into political territory; rather, it echoes a universal truth—that prolonged conflict among leaders ultimately harms the people they are sworn to serve.

The bishop’s emphasis on restraint, dialogue, and self-examination speaks to a deeper crisis of leadership. Governance driven by pride, public confrontation, and rhetorical attacks undermines trust in institutions and erodes the moral foundation of public service.

The urgency of unity becomes even more pronounced in a disaster-prone province like Catanduanes. As storms loom and communities remain vulnerable, political discord becomes more than a governance issue—it becomes a risk to lives, livelihoods, and collective resilience.

In this regard, the ELA offers a neutral and rational platform where differences can be resolved through evidence-based planning rather than emotional posturing. It provides space for both branches to align advocacies, bridge gaps, and establish a shared commitment to development beyond political affiliations.

Ultimately, the path forward demands humility, institutional discipline, and political maturity. The ELA is not merely a planning tool—it is a covenant of cooperation. When paired with moral leadership and genuine concern for the public good, it can restore harmony between the SP and the Executive and redirect Catanduanes toward inclusive, stable, and people-centered governance.